Laravel Mix creates a mix-manifest.json file that maps your asset filenames to their versioned URLs. It’s the bridge between mix('build/js/app.js') in Blade and the actual hashed filename on disk. And if you run multiple Mix builds in parallel, they’ll destroy each other.

The Problem

Imagine you have a monolith with multiple frontends — a public marketing site, a documentation site, and an internal reporting tool. Each has its own webpack config:

{

"scripts": {

"dev": "npm run dev:marketing & npm run dev:docs & npm run dev:reporting",

"dev:marketing": "mix --mix-config=webpack.mix.marketing.js",

"dev:docs": "mix --mix-config=webpack.mix.docs.js",

"dev:reporting": "mix --mix-config=webpack.mix.reporting.js"

}

}

Run npm run dev and all three compile simultaneously. Each one writes its own mix-manifest.json to public/. The last one to finish wins — the other two manifests are gone.

Result: mix('build/js/marketing.js') throws “Mix manifest not found” errors for whichever build finished first.

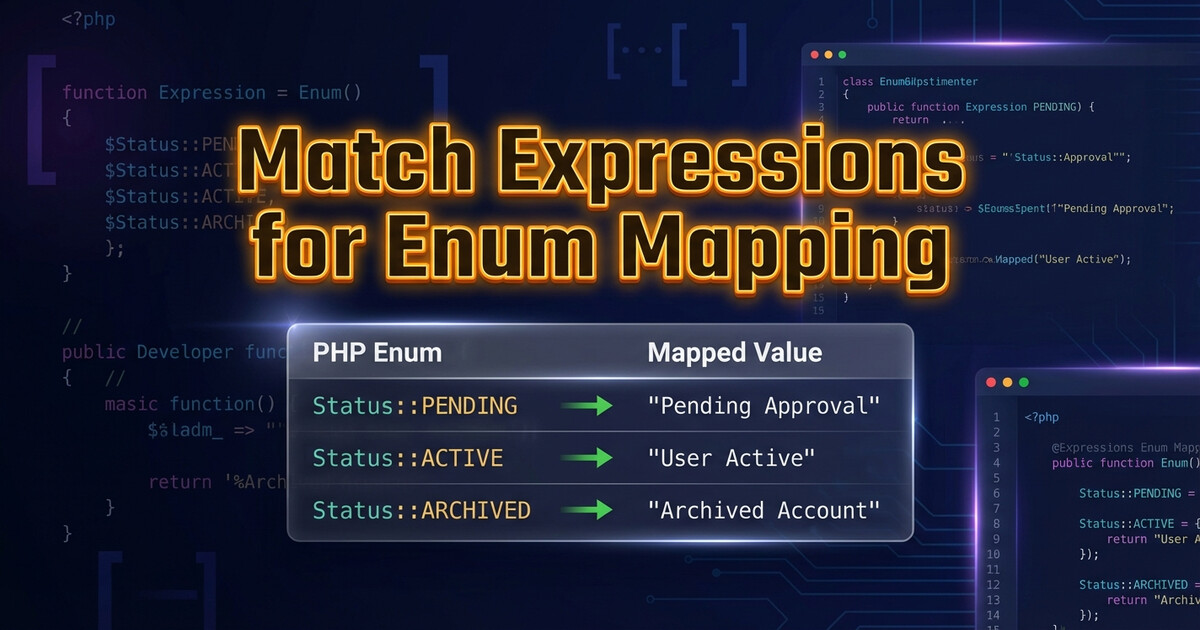

The Hot File Problem

It gets worse with hot module replacement. npm run hot creates a public/hot file containing the webpack-dev-server URL. If you run two hot reloaders simultaneously, they fight over the same file — each overwriting the other’s URL.

Laravel’s mix() helper reads public/hot to decide whether to proxy assets through webpack-dev-server. With two builds writing to the same file, only one frontend gets HMR. The other loads stale compiled assets — or nothing at all.

The Fix: Sequential Builds or Merge Manifest

Option 1: Build sequentially (simple, slower)

{

"scripts": {

"dev": "npm run dev:marketing && npm run dev:docs && npm run dev:reporting"

}

}

Use && instead of &. Each build runs after the previous one finishes. The manifest includes all entries because each build appends. Downside: 3x slower.

Option 2: laravel-mix-merge-manifest (parallel-safe)

npm install laravel-mix-merge-manifest --save-dev

Add to each webpack config:

const mix = require('laravel-mix');

require('laravel-mix-merge-manifest');

mix.js('resources/js/marketing/app.js', 'public/build/js/marketing')

.mergeManifest();

Now each build merges its entries into the existing manifest instead of overwriting. Parallel builds work correctly.

Option 3: Separate containers (best for hot reload)

For HMR, run each dev server in its own container on a different port. Each gets its own hot file context. Configure each frontend to hit its specific dev server port. More infrastructure, but zero conflicts.

The Lesson

When multiple processes write to the same file, the last writer wins. This isn’t a Laravel Mix bug — it’s a fundamental concurrency problem. Any time you parallelize build steps that share output files, check whether they’ll clobber each other.