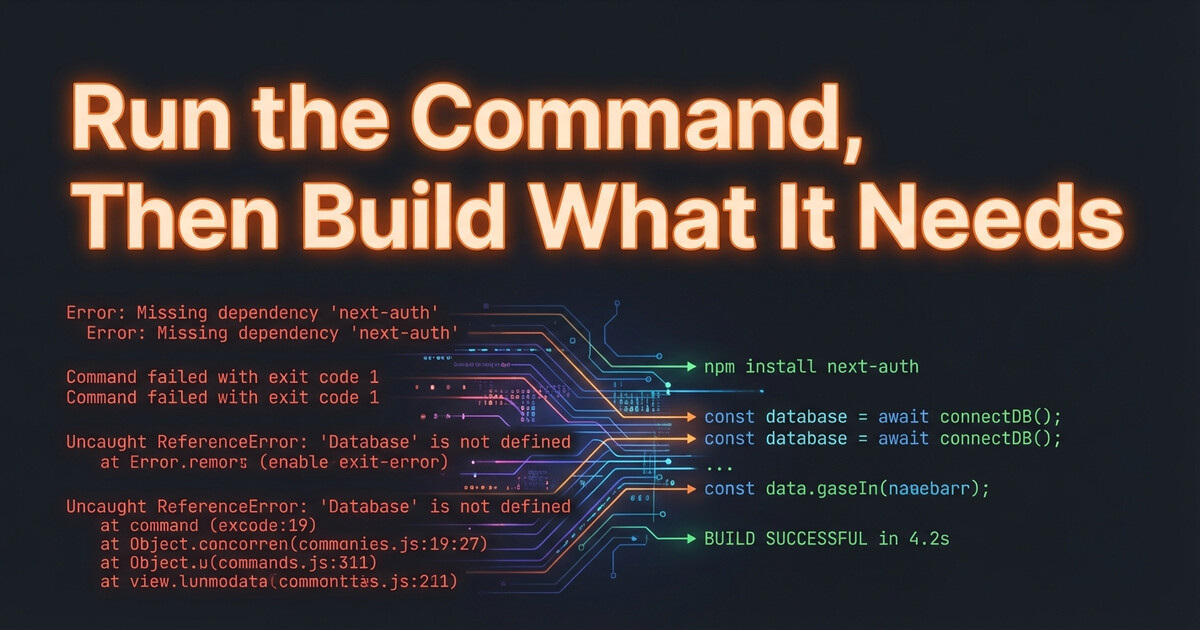

When integrating with a complex third-party API, don’t try to architect everything upfront. Start by running the integration point and let the errors guide you.

The Anti-Pattern

You read the API docs (if they exist). You design your data models. You write adapters, mappers, and DTOs. Then you finally make your first API call and… nothing works as documented.

The Better Way

Run the command first. Let it fail. Each error tells you exactly what to build next:

# Step 1: Try the API call

php artisan integration:sync

# Error: "Class ApiClient not found"

# → Build the client

# Error: "Missing authentication"

# → Add the auth flow

# Error: "Cannot map response to DTO"

# → Build the DTO from the actual responseWhy This Works

Errors are free documentation. Each one tells you the next thing to build — nothing more. You avoid over-engineering, and every line of code you write solves an actual problem.

Takeaway

Stop planning. Start running. Let errors drive your implementation order. You’ll ship faster and build only what you actually need.